The problem with definitions

This post follows a previous blogpost in which we made the case for taking a new, more rigorous look at RPG theory and in which we made our first argument as well: that if fun can be classified in a certain way, RPGs encompass at least 3 types of fun – the fun of gaming, of witnessing story-telling and of story creation itself.

In the meantime, there has been a fairly lengthy debate of the blogpost on the Tanelorn forum (german language-based, the respective threads can be found here and here) in which an old problem arose that has been marring the theoretical discussion of RPGs for a long time now: the question of how even basic terminology like games, role-playing games, story, etc. is being defined. Therefore, before continuing our efforts further below to introduce a greater amount of rigor into RPG theory, we need to have a look at these debates about definitions and the problem that definitions of even common terms pose. The basic problem here is: everyone seems to roughly know and agree what, for example, an RPG is – and yet there are frequently (at times even emotional) debates over diverging definitions… why is that the case and is there anything that can be done about it?

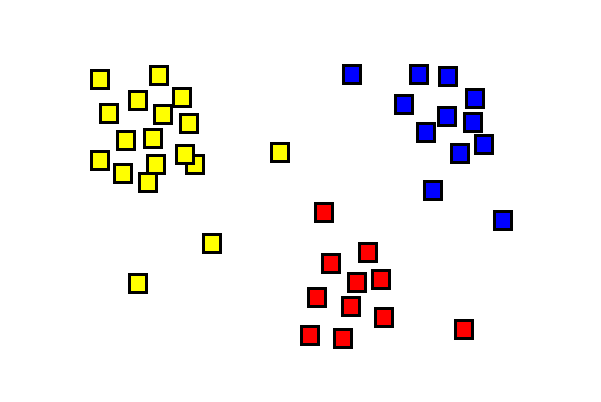

To come up with a good formal definition of, for example, “(Pen & Paper) Role-Playing Games”, one needs to single out the definining set of properties/features that all Role-Playing Games have in common but that sets them apart from other similar things (other types of games). It turns out that it is usually quite difficult to get broad consensus on what the necessary and sufficient properties are to consider a ‘thing’ being an RPG. Suppose you had a long list of all suggested candidates for these defining properties and you could rate all games according to this list of properties with sufficient accuracy. Even under such ideal conditions a precise definition of a given term might not be possible but would rather turn into a problem akin to cluster analysis.

In the above example, do the three bottom-right-most yellow squares really have to belong to the yellow cluster? Couldn’t they form their own cluster instead? Or couldn’t the most right of them be rather red instead? It depends on what algorithm you use for grouping results – and which parameters you pass to it. In the same vein, whether (for example) Fiasco is a Role-Playing Game depends on whether you require a Role-playing Game to have characters with stats recorded on a character sheet. If you do, it’s not an RPG; however, if all you require instead is players to take on a role with a distinct name and personality, it is.

As we can see, to build a formal, universal definition of Role-Playing Games we need a set of properties that makes so much sense that it gets widely accepted – which is somewhat akin to finding the right parameters so that your data points end up in crystal-clear clusters. Furthermore, to assess individual games on whether they belong, we need an equally accepted yardstick. Both are a tall order but otherwise you cannot introduce sharp distinctions where the underlying data is fuzzy. (As an aside, you can find a hint of the underlying fuzziness and the clustering being done for the sake of defining the term ‘game’ in Jesper Juul’s Game Diagram right here.)

We will never have widespread consensus if that little yellow square should be rather red.

The question then is this: do you even need to formally define common terms (like RPGs) in 99.9% of discussions? First of all, for the limited scope of a particular discussion, you can just define away outliers you don’t want to deal with – as long as you’re explicit about it and the implications for any of your subsequent results. If you don’t want to have to deal with the three yellow squares or a Fiasco-type game, it’s fine; just define RPGs to not include them for the scope of that particular debate only.

As for finding a universal definition, that’s a difficult task that is probably best left to academics in pursuit of that field. The real argument here is this: there is a common definition of (to continue our example) Role-Playing Games. It’s every bit as fuzzy as the underlying data itself but it generally works for most purposes. People who know D&D, Call of Cthulhu, FATE, Apocalypse World, the Paranoia RPG or The Pool RPG generally have a rough idea of what a RPG is, even if they can’t define it formally. Just as people probably recognize Heavy Metal when they hear it, border cases notwithstanding. They might disagree about whether the 3 yellow squares should belong or not and that’s just fine. But if you attempt to introduce a universal definition of RPGs that deviates from that common understanding of the term, you incur the burden of demonstrating why that deviation is damn necessary – for otherwise, you’re actually hindering communication instead of helping it.

As a final note, the above also explains the meaning of our finding in Part 1: when Conclusion 1 states that “RPGs encompass at least 3 types of fun” it does not imply that every RPG must encompass all 3 types. Instead, it states that the statement holds true for much of that rough cluster we call Role-Playing Games and that this may or may not be true for any outlier games. It is merely generally true for that type of games.

Part 2: From types of fun to personal clashes

Axiom 6: The different types of fun provided by RPGs can come into conflict with each other during gameplay.1

Assumption 2: Different role-players may have different preferences when it comes to the types of fun in RPGs.2, 3

Assumption 3: Conflicting types of fun get resolved internally based on such a personal, subjective order of preference and, in the case of a clear resolution in such a situation, a given course of action will be preferred if not advocated for.4

Definition 1: We will call any factors that impact a participant’s decision in a conflict-of-fun situation beyond these personal preferences external factors or externals.

Conclusion 2: Based on divergent preferences regarding types of fun, different participants might prefer different courses of action in a given situation to maximize their own fun, regardless of any external factors. Under these circumstances, the divergent preferences may cause a conflict between participants.

The argument here is that if, for example, you have two participants who strongly favor two different types of fun and there is a conflict-of-fun situation that promises to greatly entertain one participant at the price of stark enough disappointment for the other, it cannot be assumed that the participant who eventually loses out (the group’s consensus goes against him) will necessarily acquiesce.

1 Note that this is true by default until evidence to the contrary emerges.

2 This means in particular that (until evidence to the contrary emerges) there is no universal order of preference that all role-players ascribe to.

3 Further note that this does not necessarily imply that any order of preference is necessarily stable (consistent) in time. Nor does any order of preference necessarily mandate choices being made strictly to appeal to the highest applicable preference – a choice of action that promises to enhance a lower ranked type of fun greatly might be perceived as favorable to a choice of action that enhances a higher ranked type of fun minimally.

4 Note that this does not imply that these preferences are the only relevant factors that can impact a participant’s decision on which course of action to take in a clash-of-fun situation. For example, Jamie might normally enjoy the gaming aspects in RPGs the most. But when faced with a situation where it comes into conflict with the story-telling, he might end up choosing the course of action that gives preference to the latter – only because playing to the gaming side in this instance would benefit Michael and Jamie doesn’t like Michael. The personal antipathy outweighs the fun preferences.

Leave a Reply